Building Communities: Choose a Cause, Make a Choice

Imagine attending a crowded meeting with hundreds of enthralled listeners. An emotional orator tries to persuade you to support his social cause, join his church, or political party. During the early 1800s, many Vermonters attended such meetings and made major life-altering decisions at them.

Are You Saved?

Social and economic upheavals in Vermont sparked a wave of intense religious fervor. Great competition arose between old denominations and many new faiths. Revivals, passionate emotional gatherings led by charismatic preachers, were conducted in churches, large tents, and clearings in the countryside. These meetings could last for days as people listened to sermons and prayed collectively. Revivals peaked around 1831. The main beneficiaries of this increased spirituality were established evangelical churches such as the Methodists and Universalists. The era also witnessed the creation of new sects and religions. Many of them failed, but some succeeded and prosper to this day, such as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (also known as Mormons) and Seventh-Day Adventists.

Evil Rum

As in the rest of America, drinking was a common practice in eighteenth-century Vermont. Alcohol was part of everyday life, and getting drunk was a common occurrence at public events such as militia musters. Increasingly, though, people began to see drinking as the cause of many of society’s problems. Early in the nineteenth century growing numbers of Vermonters began practicing moderation or complete abstinence.

As in the rest of America, drinking was a common practice in eighteenth-century Vermont. Alcohol was part of everyday life, and getting drunk was a common occurrence at public events such as militia musters. Increasingly, though, people began to see drinking as the cause of many of society’s problems. Early in the nineteenth century growing numbers of Vermonters began practicing moderation or complete abstinence.

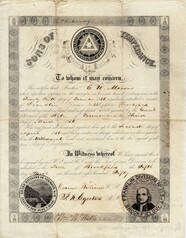

Middle-class reformers founded the Vermont Temperance Society, which advocated complete sobriety, in 1828. By the late 1830s, temperance advocates were working to pass laws making the sale of alcohol illegal. Laws partially limiting the manufacture and distribution of alcoholic beverages drew heated opposition from some Vermonters, particularly in rural districts. Nevertheless, temperance reformers won when a law mandating the total prohibition of alcohol passed by a narrow margin in an 1853 referendum.

Antimasonry

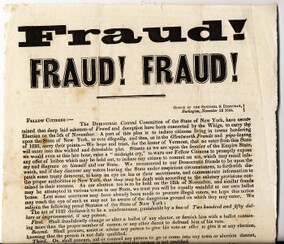

The antimasonic movement found its most receptive audience and greatest political success in Vermont. This movement began after the disappearance and assumed murder in Canandaigua, New York, of a man who threatened to reveal in print the rituals of the Free Masons, a secret fraternal society. The affair provoked widespread anger and suspicion at the institution, which was seen as antidemocratic. This was especially true in Vermont. Many of the Masons were merchants and professionals who held influential political positions and seemed to be benefiting from changes in Vermont’s economy.

Citizens who felt frustrated by limited opportunities and increasing social and economic inequalities lashed out at the organization. Antimasonry grew into an insurgent political movement; the Antimasonic Party was America’s first major third party. Vermont gave its electoral votes for president to the Antimasonic candidate in 1832, and in four consecutive elections for governor beginning in 1831. The movement quickly declined after that, however, and most antimasons drifted into the Whig Party—but not before most Masonic chapters closed.

Citizens who felt frustrated by limited opportunities and increasing social and economic inequalities lashed out at the organization. Antimasonry grew into an insurgent political movement; the Antimasonic Party was America’s first major third party. Vermont gave its electoral votes for president to the Antimasonic candidate in 1832, and in four consecutive elections for governor beginning in 1831. The movement quickly declined after that, however, and most antimasons drifted into the Whig Party—but not before most Masonic chapters closed.

Democracy in Action

By the early 1820s, the first two-party system in America had collapsed. The Federalist and Jeffersonian-Republican Parties had fractured under the weight of divisive issues. In Vermont, political parties were divided over the issues of slavery, tariffs, and monetary systems, as well as temperance, women’s rights, Masonic membership, imprisonment for debt, Sabbath laws, and education. The Whigs were the dominant party in Vermont from the late 1830s to the early 1850s. But they held such a narrow majority that eight gubernatorial elections during that period were decided by the legislature when no candidate won a majority vote as required by the constitution. These hotly debated issues brought more Vermonters than ever before into the political process, although women still could not vote.

Abolition

Slavery was the most contentious and inflammatory issue Vermonters confronted in this era. Click here to learn more.

Images: (top) Sons of Temperance membership certificate issued in 1850 by Brookfield’s Franklin Chapter.

(bottom) Illustration from the Anti-Masonic Almanac for 1830.