Building Communities: Wool and Cheese

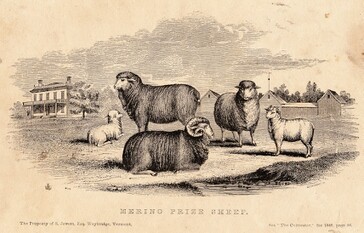

Farming was changing by the 1820s. Small subsistence farms that raised a variety of crops and animals were being replaced by larger, more specialized farms with a more commercial orientation. More Vermonters began raising sheep and cattle, and growing hay and corn to feed them. The demand for sheep’s wool boomed in the 1820s as the textile industry expanded. Vermont was swept up in the sheep craze. By 1837 there were over one million sheep in the state.

Farming was changing by the 1820s. Small subsistence farms that raised a variety of crops and animals were being replaced by larger, more specialized farms with a more commercial orientation. More Vermonters began raising sheep and cattle, and growing hay and corn to feed them. The demand for sheep’s wool boomed in the 1820s as the textile industry expanded. Vermont was swept up in the sheep craze. By 1837 there were over one million sheep in the state.

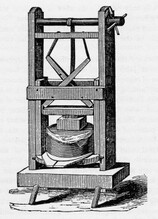

Cheese and butter production became an increasingly important part of Vermont’s agricultural economy. Almost all Vermonters had cows. Making butter and cheese was a way to use milk before it spoiled. Tubs of butter and wheels of cheese were produced by farmers and sold or traded for manufactured goods at local stores. Merchants in turn would ship these dairy products to cities like Boston and New York, and exchange them for items to stock their stores. Cheese and butter became the main cash commodity of many farms, especially as the demand for wool declined by mid-century.

Cheese and butter production became an increasingly important part of Vermont’s agricultural economy. Almost all Vermonters had cows. Making butter and cheese was a way to use milk before it spoiled. Tubs of butter and wheels of cheese were produced by farmers and sold or traded for manufactured goods at local stores. Merchants in turn would ship these dairy products to cities like Boston and New York, and exchange them for items to stock their stores. Cheese and butter became the main cash commodity of many farms, especially as the demand for wool declined by mid-century.

Agricultural specialization would forever change Vermont. Most Vermonters still depended on agriculture for a living in 1840, when four out of five men were farmers. Market forces beyond the state’s borders often determined the success or failure of a farm. Livestock required large pastures for grazing, which led to more clear-cutting of forests and rising land values. As Vermont’s farming communities matured, many young people found that they had to leave home to find affordable farmland in the west, or work in the cities.

Images: (top) Illustration of prize merino sheep owned by S. Jewett of Weybridge, Vermont as featured in The Cultivator (1846).

(bottom) Cheese press.

Explore More