Building Communities: Work in Transition

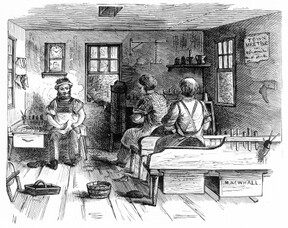

Abdiel Kent’s shoe shop represents a time in Vermont when local craftsmen met local needs. These shop owners not only made a product but also provided work for young farm men and some women when their help wasn’t needed at home.

Born at Kent’s Corner in Calais in 1805, Abdiel Kent was one of seven children. Like many young men of his generation, Kent left home in his teens, working as a mason in New Hampshire and a shoemaker in Massachusetts. When he returned home in the late 1820s, he opened a shoe and boot manufacturing shop. For the next thirty years, Kent and his family prospered, expanding Kent’s Corner to include a store, barns for a blacksmith and harness shop, and a large brick inn. They also farmed, built houses, and ran a brickyard down the road at Gospel Hollow. Kent was a community leader, serving as a selectman, as town moderator, and representing Calais in the state legislature.

Born at Kent’s Corner in Calais in 1805, Abdiel Kent was one of seven children. Like many young men of his generation, Kent left home in his teens, working as a mason in New Hampshire and a shoemaker in Massachusetts. When he returned home in the late 1820s, he opened a shoe and boot manufacturing shop. For the next thirty years, Kent and his family prospered, expanding Kent’s Corner to include a store, barns for a blacksmith and harness shop, and a large brick inn. They also farmed, built houses, and ran a brickyard down the road at Gospel Hollow. Kent was a community leader, serving as a selectman, as town moderator, and representing Calais in the state legislature.

Workers at Kent’s Shoe Shop

Kent’s account books and the census records shed light on his employees. Kent hired locals as well as young men who boarded with him. Five to six men could work in the shop at a time, and over the years dozens of different men labored there. Kent paid them an average of five dollars a week, deducting board and any expenses they might owe him.

Curtis Mower was a local farmer who occasionally worked for Kent, with frequently excused absences for haying, planting, militia training, and town meeting.

Roxa Tucker was a sixteen-year-old who lived up the road from Kent on her parents’ farm. She probably didn’t work in the shop, but took home piecework, like several married women in the community.

Joel Langdon, a twenty-one-year-old boarder, represented the more typical worker of the era who made shops like Kent’s viable. He wasn’t married, didn’t own property, and hadn’t settled on a career, but he needed to earn a living while deciding what to do with his life.

The End of an Era

When Kent first opened his shop he was selling his shoes not only in Calais, but also in Montpelier. But local artisans began facing increased competition in the 1830s when cheaper imports from southern New England became available. Prices dropped in the 1840s as shoemaking became more mechanized, allowing mass production. Many small shops went out of business because they couldn’t compete with the lower prices or offer the variety of styles. Abdiel Kent adapted by closing his shoe shop and expanding his general store.

When Kent first opened his shop he was selling his shoes not only in Calais, but also in Montpelier. But local artisans began facing increased competition in the 1830s when cheaper imports from southern New England became available. Prices dropped in the 1840s as shoemaking became more mechanized, allowing mass production. Many small shops went out of business because they couldn’t compete with the lower prices or offer the variety of styles. Abdiel Kent adapted by closing his shoe shop and expanding his general store.

Rural communities formerly crowded with shops, mills, and stables changed as population loss accelerated by the 1850s. Sons and daughters who couldn’t afford farms moved west where land was cheaper, or into Vermont’s growing urban centers where work was available.

Images: (top) Abdiel Kent

(bottom) Interior of a shoe shop with workers from the mid-nineteenth century.

Explore More