Creating an Image: Open Roads

Though railroad lines reached most of the major cities and towns in Vermont by 1900, visitors and residents alike still usually found themselves riding in horse-drawn wagons to get to their final destinations. However, many saw the potential of the automobile for tourism and forward-thinking farmers recognized the value of trucking and improved roads for transporting goods to market. Founded in 1903, the Automobile Club of Vermont promoted automobile users’ rights, maintained a social club, and most importantly, advocated for road improvement.

In addition to tourist vehicles, more than 37,000 registered cars called Vermont home in 1920. With the devastation of the railroads caused by the 1927 Flood and growing public support for and dependence upon automobiles, increased state support for road improvement and construction took off.

In addition to tourist vehicles, more than 37,000 registered cars called Vermont home in 1920. With the devastation of the railroads caused by the 1927 Flood and growing public support for and dependence upon automobiles, increased state support for road improvement and construction took off.

Jackson’s Drive

Over the summer of 1903, Dr. Horatio Nelson Jackson of Burlington, Vermont, became the first person to drive an automobile across the continental U.S. On a trip to San Francisco in May of 1903, Jackson, who had been taking driving lessons in the city, made a $50 wager that he could drive an automobile across the country.

With virtually no mechanical experience, Jackson hired Sewall K. Crocker as his mechanic, travel companion, and back-up driver. Driving a used, two-cylinder, twenty horsepower Winton automobile christened the Vermont, Jackson and Crocker set out from San Francisco and followed the northerly route of the Oregon Trail. The roads were rough and the car regularly needed repairs and supplies, often provided by horse and wagon. With no good maps, Jackson had to rely on directions from people he met along the way, often resulting in significant detours.

By the time they reached Idaho, word had gotten out about the trip and people began following their progress in the press. Along the way they picked up a pitbull named Bud who became an unofficial mascot of the trip.

By the time they reached Idaho, word had gotten out about the trip and people began following their progress in the press. Along the way they picked up a pitbull named Bud who became an unofficial mascot of the trip.

On July 26, they arrived in New York City, 63 days, 12 hours, and 30 minutes after the start of their journey. After much celebration, Jackson made his way back to Burlington where Vermont’s drive chain, one of the few original parts to make the journey, snapped.

Jackson’s drive proved that automobiles were not a passing fad and helped to encourage the building of infrastructure to support motor vehicle travel throughout the U.S. Though he won the bet, Jackson never collected his winnings.

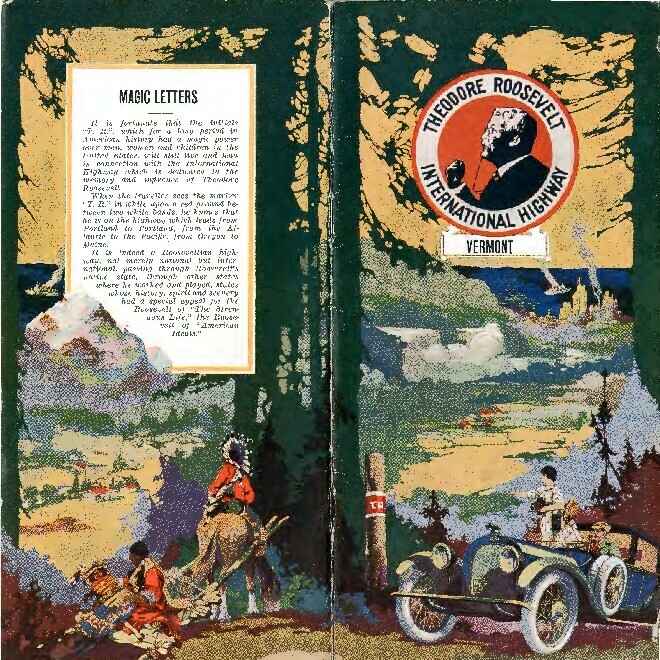

Theodore Roosevelt International Highway

Before the advent of federal highway systems, regional automobile clubs took on the task of mapping autoroutes out of existing roads for the benefit of their members and the growing tourist trade. In some cases, these regional projects expanded to clubs across the country, creating the first nationwide road systems.

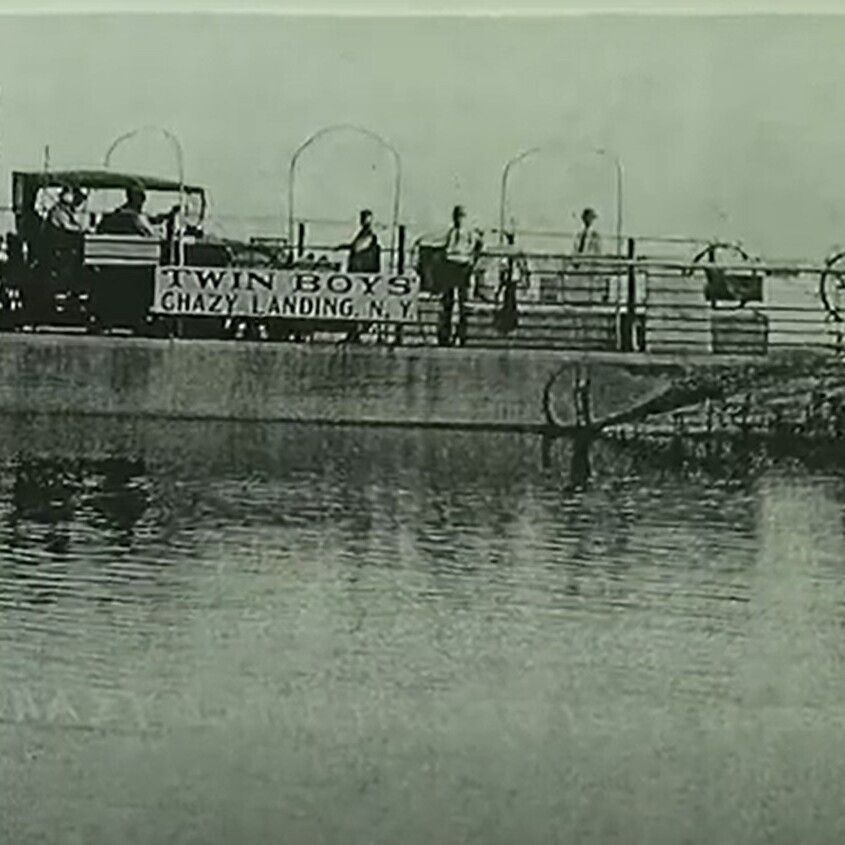

Shortly after Theodore Roosevelt’s death, automobile clubs in Minnesota applied for state permits to create an auto trail named in his honor. The project soon expanded to clubs throughout the northern states with trail marking mostly finished by the end of 1919. In Vermont, the trail started in Waterford on the New Hampshire border and ended in South Hero where a ferry transported travelers to the New York portion of the route. Colored bands on telephone poles or small metal signs marked the autoroute.

The Highway was managed as a private promotional concern until 1925 when the federal Interstate Highway Commission designated the trail as U.S. Route 2. In Vermont, much of modern Route 2 follows the same roads as the original Roosevelt Highway.

Images: (top) Mud season in Vermont during the early twentieth century.

(bottom) Dr. H. Nelson Jackson at the wheel with mechanic Sewall Crocker and Bud the dog in their automobile Vermont.

Explore More

This page was originally created as part of the Vermont Historical Society’s Freedom & Unity exhibit in 2006. Some materials may have been updated for this 2021 version.