Early Aviation, 1910

Following news of the Wright Brothers’ exciting success at Kitty Hawk, exuberant Vermont youths took to their garages and workshops to construct their own flying machines.

Background information

According to Cora Cheney, in her Profiles from the Past, teenagers George Schmitt of Rutland and Charles Hampson Grant of Peru built gliders using ordinary wire, muslin, and light wood, and successfully flew them from the roofs of their houses in 1909 and 1910 respectively. Hooked on the thrill, both progressed shortly thereafter into motorized air flight, with Schmitt earning the dubious distinction of becoming Vermont’s first air fatality as a result of his Rutland crash in 1913.

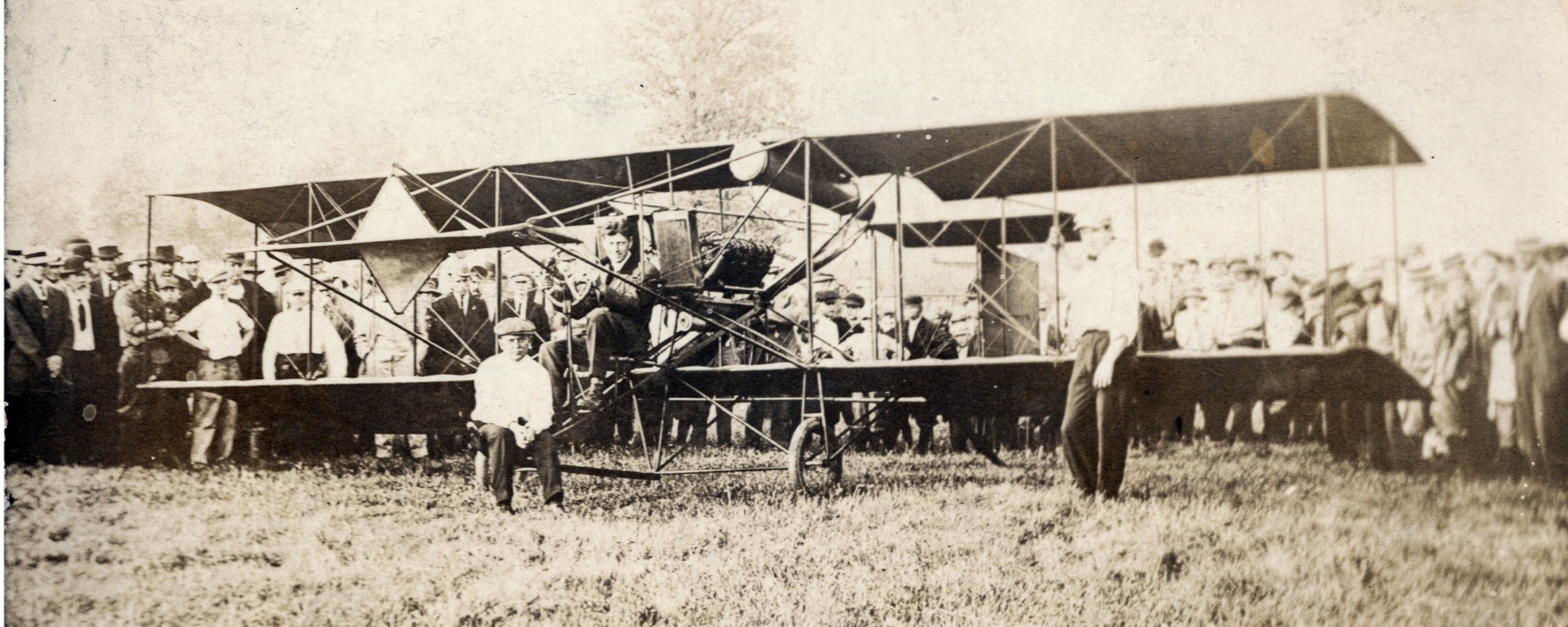

That planes during this era were an unusual curiosity in Vermont, Cheney notes, was amply demonstrated during September, 1910, when 10,000 people traveled to the Caledonia State Fair grounds to go watch barnstormer Charles Willard fly in a Curtiss bi-plane as the first “sustained heavier than air flight in Vermont.”

Youths were not the only ones captivated by this marvelous new contraption. Aged 55 in 1916, James Hartness, head of Springfield Tool and Die and later governor of Vermont, received his amateur pilot’s license, and three short years later, purchased two farms in North Springfield for the purpose of creating Vermont’s first airport. To celebrate the event, Hartness arranged for Boston barnstormer and ex-Navy flier ensign Terhune to fly to the airport on July 3rd at noon and give rides to passengers throughout the following day’s celebration. In this infant age of air travel, Hartness’ plan was implemented only with considerable difficulty. Setting out from Swampscott, Massachusetts, toward Springfield in a thick haze, Terhune courageously attempted to guide his craft with only limited assistance from his primitive instruments. Several hours into the flight, however, when the haze broke, he found himself to his dismay over the Atlantic Ocean. Recognizing his error, he reversed direction and managed to pilot the plane within sight of Worcester; but again, fog and haze obscured his view. Finally, over Windsor Locks, Connecticut, he was able to regain his bearings and, refueling in Chicopee, Massachusetts, was successful in following the Connecticut River to Springfield, Vermont, where he landed some five hours late.

Yet Terhune’s difficulties were not yet over. After successfully taking three passengers on short excursions around the field, including the president of the Vermont State Federation of Women’s Clubs and the superintendent of the Colonial Light and Power Company, Terhune relinquished control of the plane to a Lt. Parker, newly sent from Boston to relieve him. As Terhune watched, Turner commenced an unsteady takeoff. A few short seconds after leaving the ground, the plane crashed, completely wrecking it, though, mercifully, leaving Turner and his passenger uninjured.

Hartness’ flying school, organized in 1921, bolstered the ranks of Vermont’s flyers, yet air gravel retained an aura of unpredictability and danger. In October 1923, Frank Gibson was forced to make an emergency landing on a local Springfield farm when his engine quit on him. Correcting the problem, Gibson realized, to his dismay that the field in which he had come down was too small to permit a takeoff. His solution: disassemble the machine and haul the parts to the municipal landing field for reassembly.

Charles Lindbergh’s monumental transatlantic flight (May 20-21, 1927) and his subsequent visit to Vermont on July 27, 1927, where he met with Hartness, followed by a depression whose numbing bleakness cried out for “heroic” diversions, fanned the fires of Vermonters’ imaginations and gave rise to a somewhat bizarre, albeit unsuccessful 1932 venture to fly from the Barre-Montpelier airport to Oslo, Norway. The circumstances surrounding the flight bear retelling. It appears that a local granite operator, Robert Bassett, arranged with a Midwestern barnstorming pilot by the name of Clyde Lee, to undertake the flight in August 1932. In an era when businessmen sponsored transatlantic flights for publicity, Bassett arranged with area businessmen to raise $1,000, or one-half the projected cost. Businessmen in Oslo paid the other half. Lee was promptly flown in and his red plane repainted and renamed “Green Mountain Boy,” with the title “Granite Capital of the World” recorded in a circle below.

Charles Lindbergh’s monumental transatlantic flight (May 20-21, 1927) and his subsequent visit to Vermont on July 27, 1927, where he met with Hartness, followed by a depression whose numbing bleakness cried out for “heroic” diversions, fanned the fires of Vermonters’ imaginations and gave rise to a somewhat bizarre, albeit unsuccessful 1932 venture to fly from the Barre-Montpelier airport to Oslo, Norway. The circumstances surrounding the flight bear retelling. It appears that a local granite operator, Robert Bassett, arranged with a Midwestern barnstorming pilot by the name of Clyde Lee, to undertake the flight in August 1932. In an era when businessmen sponsored transatlantic flights for publicity, Bassett arranged with area businessmen to raise $1,000, or one-half the projected cost. Businessmen in Oslo paid the other half. Lee was promptly flown in and his red plane repainted and renamed “Green Mountain Boy,” with the title “Granite Capital of the World” recorded in a circle below.

On the morning of August 23rd, Lee and his co-pilot, a native Norwegian named John Bochkon, left Barre bound for Harbor Grace, Newfoundland. At the same time, another plane carrying two Norwegian-American pilots, Thor Solberg and Cal Peterson, departed from New York on a similar mission to Oslo. The race was on. It did not, however, last long. Flying into a fogbank, Solberg and Peterson crashed their plane off the shore of Newfoundland and were rescued by a passing fisherman. The race was over.

Lee and Bochkon successfully landed their plane on a beach at Burgeo, Newfoundland, and with the lifting of the fog, managed to continue to Harbor Grace, where they dispatched a telegram to Barre telling of their safe arrival. The following day (August 25), after refueling their plane, they commenced the main leg of the trip. They departed Harbor Grace at 5:02 a.m., enjoying clear weather and favorable tail winds, carrying sandwiches, two-and-a-half gallons of water, a quart of milk, a pint of coffee, concentrated food tables, and 200 gallons of gasoline in five-gallon cans. Calculating an average air speed of 114 mph, the pilots expected their thirty-two hour flight would bring them to Oslo the following day at noon.

When the noon touchdown failed to materialize, their navigator, Henry Huntington, expressed little concern, pointing out that the plane was loaded with enough gasoline for five additional hours of flying time. Later in the afternoon, in Norway, King Haakon ordered flying boats of the Norwegian Air Force to patrol the coast, while officials at the Kjeller airfield, where Lee and Bochkon were expected to arrive, erected eight floodlights on the runway and set a large bonfire as a beacon to guide the plane in.

As night gave way to daybreak, promoters in Barre’s Granite City Auto Sales showroom remained confident that the men were safe. The plane, Huntington observed, was capable of a sea landing, and could be kept afloat for two weeks by the eighty-five gallon gas cans which presumably had been emptied during the flight. Moreover, the plane was outfitted with kites and flares to signal for help.

But the passage of time produced no signals of the plane’s whereabouts and the Green Mountain Boy and its two passengers were never found. With the failure of the flight, Barre promoters found themselves unable to redeem the pledges of backing, and Robert Bassett, who had masterminded the scheme, was obliged to pay bills in excess of $500 out of his own pocket.

Further reading

Cora Cheney, Profiles from the Past: An Uncommon History of Vermont. Taftsville, Vt.: Countryman Press, 1976.

Charles Hampson Grant [sound recording] / interviewed by Cora Cheney Partridge. [Montpelier, Vt.: Vermont Historical Society], 1975. 2 sound cassettes (90 min.). Recorded in March, 1975 in Mr. Grant's home in Manchester, Vt. Summary notes available, MSA 251. William H. and Edna Dashner Adams Oral History Cataloging Project, 2001.

Haskins, Harold W., “A Noteworthy Airplane Flight.” Bradford Historical Society brochure, no. 2 (May 1970).

William H. Soule, “The Green Mountain Boy: An Attempted Trans-Atlantic Flight from Vermont to Norway, 1932,” Vermont History 42 (Fall 1974): 311-317.

Citation for this page

Woodsmoke Productions and Vermont Historical Society, “Early Aviation,” The Green Mountain Chronicles radio broadcast and background information, original broadcast 1988-89. https://vermonthistory.org/early-aviation-1910