The 4-H in Vermont, 1914

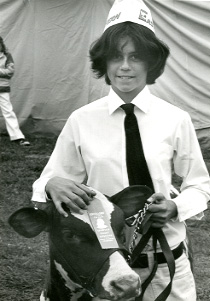

With the decline of the Grange movement during the early part of the twentieth century, new instruments were developed to sustain the vitality of Vermont’s agricultural community. The Smith-Lever Act, passed by Congress in 1914 to provide for “the advancement of agriculture,” funded the fledgling Vermont Extension Service, operating under the aegis of the University of Vermont. Monies were channeled into three broad program areas, each to be administered by the Extension Service. The first was designed to promote extensive agricultural experimentation, the second sponsored “home demonstrations” across the state to acquaint farm families with innovations in “scientific” farming, and the third organized boys’ and girls’ clubs to “teach them how to manage, grow, and prepare market crops and animals and to demonstrate how to save surplus products by home canning.” Lest this language prove somewhat less than alluring, 4-H clubs, specifying “head, heart, health, and hands,” were born.

Oral history transcriptions

Click a name below for more information. All transcripts are in PDF format.

Background information

Its founders comprised a rather disparate group, including a Mrs. John Chase, organizer of the Lyndon Garden Class, Archibald Hurd, secretary of the Windsor County YMCA, two school superintendents, Sherburne Hutchinson (Montpelier), and Phil Leavenworth (Castleton), two rural preachers, C. O. Gill (Hartland) and John Sherby (Hartford), and a UVM professor, Floyd B. Jenks, who was appointed part-time state agent in charge of the 4-H program. For all intents and purposes, however, the true genius behind the movement’s success was its first full time state leader, Elwin L. Ingalls, who held the position for thirty years (1914-1944).

Its founders comprised a rather disparate group, including a Mrs. John Chase, organizer of the Lyndon Garden Class, Archibald Hurd, secretary of the Windsor County YMCA, two school superintendents, Sherburne Hutchinson (Montpelier), and Phil Leavenworth (Castleton), two rural preachers, C. O. Gill (Hartland) and John Sherby (Hartford), and a UVM professor, Floyd B. Jenks, who was appointed part-time state agent in charge of the 4-H program. For all intents and purposes, however, the true genius behind the movement’s success was its first full time state leader, Elwin L. Ingalls, who held the position for thirty years (1914-1944).

Within a single year after taking over the reigns of leadership, Ingalls’s indefatigable labors crisscrossing the state (though no figures are available for 1914, Ingalls in his 1916 report noted that he had traveled 12,064 miles by rail, 950 by automobile, and 159 by foot) translated into the chartering of 80 clubs in 65 towns throughout Vermont, with a membership in excess of 5,000 boys and girls. Visiting Schools, granges, and wherever else he could wrangle an invitation, Ingalls initially created 12 projects to serve the goals set forth by the club. Participation, though not formally mandated, was nevertheless organized along gender lines. Male participants were introduced to “scientific” crop and animal production (corn, potatoes, maple sugaring, poultry, lamb, calf production), while females were encouraged to develop domestic skills (bread baking, handicrafts, sewing, home gardening). As late as 1942, clothing projects engaged 2,222 girls and 13 boys, with the figures reversed for crop production.

When America entered World War I, Ingalls quickly raised the banner of patriotism and rallied his youthful corps around a “Win the war program” designed to organize community canning kitchens, with the intent of preserving surplus food for foreign and domestic consumption.

When America entered World War I, Ingalls quickly raised the banner of patriotism and rallied his youthful corps around a “Win the war program” designed to organize community canning kitchens, with the intent of preserving surplus food for foreign and domestic consumption.

With the cessation of hostilities in 1918, the 4-H continued to flourish, albeit with different emphases. Competitions were instituted in the form of “demonstration teams,” with winning teams being permitted to compete in the annual Eastern States Expo. Similarly, prizes were awarded at the annual state fair in Rutland to recognize outstanding projects.

During the prosperous 1920s, new four-year programs were developed. The program for girls encouraged them to further hone their homemaking skills. In the first year girls assembled a complete outfit; over the course of the succeeding three years they sewed accompanying items and kept a complete budget of their expenses. Another program focused on health skills, such as learning to prepare meals using dairy items. Programs for boys helped them learn the intricacies of farming, such as soil testing, keeping records, etc. Other new programs included the production, packaging, and sale of one-ounce maple sugar cakes across the country, the development of forestry management classes, and the proper care of poultry production. In addition, during the summer of 1929, nine camps were established, each permitting one or two leaders appointed by local clubs to engage in a week’s worth of work (i.e., learning about hygiene from guest lecturers) and fun (arts, crafts, nature walks).

With the onset of the Great Depression, 4-H underwent still another transformation. “With the decreasing amount of cash available for family living,” the 1930-1931 annual report noted, “the problem of providing recreation at a time when it is most needed to keep up the morale of the individuals seemed worth of special attention.” Consequently, emphasis was placed upon diversions ranging from games, contests, plays, and singing events. In addition, new camps were organized at Lake Salem in Orleans County, Townsend, and Sunderland.

Once again, with the outbreak of war, 4-H’ers demonstrated their patriotic fervor by sponsoring scrap drives and “victory gardens.” Reports of pork shortages led to an active campaign culminating in the raising of 592 pigs. In addition, the more than 10,000 male and female participants of 4-H across the state produced clothing, canned food, served as hospital aides, created scrapbooks for hospitalized servicemen, and sent seeds to the needy in war-torn Europe.

The post-war era witnessed still further changes, as the 4-H movement continued to march in step with the times. In 1949, the first 4-H band was formed in Chittenden County under the guidance of the UVM band director, with others formed during the 1950s to perform at parades and other social events. With a growing awareness of the civil rights movement during the 1960s, 4-H’ers in 1967 invited fifty urban ghetto youths to participate in 4-H summer camps. And, amid increased environmental awareness during the 1970s, 4-H projects were developed to include study of water quality, air pollution, pesticides, fire control, and wildlife and soil conservation. Moreover, for a movement dedicated to the preservation of rural life, it is rather fascinating to observe that, by 1980, fully one-fourth of all 4-H club members resided in towns with populations over 10,000 residents. As of 2011, Vermont has 95 4-H clubs located throughout the state.

Further reading

Lisa Halvorsen, Highlights of the Vermont Extension Service (Burlington, 1982).

Vermont Extension Service, Annual Reports, 1915-1947.

Citation for this page

Woodsmoke Productions and Vermont Historical Society, “The 4-H in Vermont,” The Green Mountain Chronicles radio broadcast and background information, original broadcast 1988-89. https://vermonthistory.org/4-h-in-vermont-1914