The Anarchist Movement in Barre, 1920

Oral history transcriptions

Click a name below for more information. All transcripts are in PDF format.

Background information

For a few years prior to World War I, Barre was a center for anarchist ferment in the United States. It was a time of rapid growth for Barre village and town, with the population increasing by 73 percent between 1890 and 1900, and another 27 percent from 1900 to 1910. Barre’s expanding granite industry fueled this population boom, composed largely of foreign-born skilled stone-cutters and quarrymen from Scotland, Spain, and especially northern Italy, making it Vermont’s preeminent melting pot, blue-collar community. By 1914, almost one-quarter of the town’s population was Italian.

For a few years prior to World War I, Barre was a center for anarchist ferment in the United States. It was a time of rapid growth for Barre village and town, with the population increasing by 73 percent between 1890 and 1900, and another 27 percent from 1900 to 1910. Barre’s expanding granite industry fueled this population boom, composed largely of foreign-born skilled stone-cutters and quarrymen from Scotland, Spain, and especially northern Italy, making it Vermont’s preeminent melting pot, blue-collar community. By 1914, almost one-quarter of the town’s population was Italian.

Labor radicalism in Barre accompanied the town’s population growth. The new arrivals brought with them, more or less intact, political views shaped by bitter economic experience in the old country. As a result, trade unionism came early to Barre. By 1899, 90 percent of the town’s wage earners were members of one or another of the area’s fifteen local unions. The diverse population made for a variety of radical political beliefs generally reflecting the community’s immigrant groupings, as each strove to keep its own identity by forming its own social and political clubs and reading newspapers in the language of the old country. A large number of Barre’s union men considered themselves socialists, an identification that was popular in town through the 1930s. Most of the nationally known radical leaders came to Barre at one time or another, including the labor organizer, Mother Jones; Socialist Party presidential candidate, Eugene V. Debs; and labor radical William “Big Bill” Haywood.

Of the various political radicals, Barre’s anarchists were few in number and Italian in origin, but their presence was strongly felt. Although there were groups of Italian anarchists in other granite industry towns, such as Montpelier, Northfield, and Hardwick, Barre possessed the largest and most important contingent. Italian language anarchist newspapers were published there, one of which was edited for a time by Carlo Abate, a gifted sculptor and labor intellectual. Emma Goldman, a leader in the U.S. anarchist movement, made two trips to Barre for speaking engagements. In her autobiography, she described her first Barre visits, in June 1899. Goldman recalled that the anarchist “group there consisted of Italians employed mostly in the stone quarries” and that her Barre host “was a cultivated man, well-informed not only on the international labor movement but also on the new tendencies in Italian arts and letters.” Although she was scheduled to present a series of lectures, Barre’s mayor intervened to prevent Goldman from completing her engagement after she had delivered only two presentations (each to packed houses). In 1907, Goldman returned to speak to an audience of 500 people at the Barre Opera House.

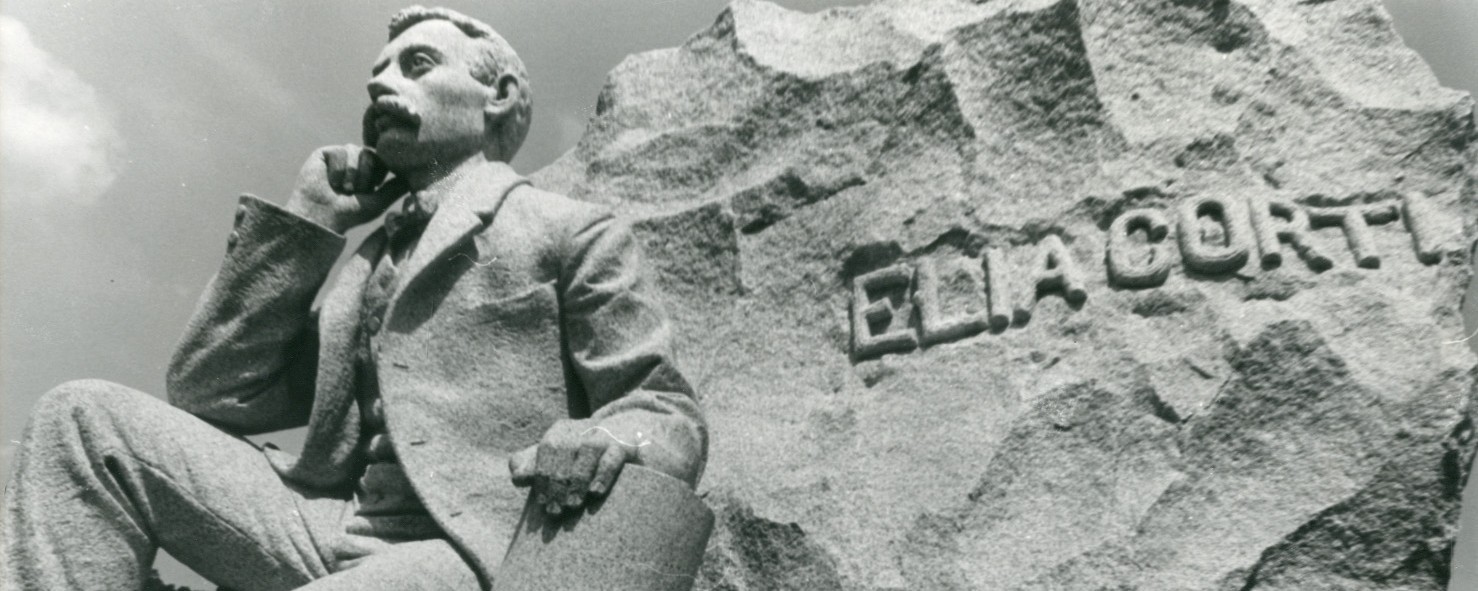

An incident of anarchist-related violence in 1903 reflected tensions that existed between Barre’s pre-World War I anarchist and socialist factions. The feud was apparently rooted in a dispute over upkeep and control of the town’s Socialist Hall on Granite Street. An Italian socialist newspaper editor from New York City with an anti-anarchist reputation had been invited to speak at the hall. When the speaker’s arrival was delayed, a fight broke out, gun shots were fired, and one of the town’s leading sculptors, Elia Corti, was accidentally killed. The violence associated with European anarchists was nevertheless not characteristic of anarchists in Barre. The Barre Daily Times of the period found local anarchists to be “good citizens in that they were peaceable, honest men who mind their affairs, pay their bills, and have no desire to trouble anyone, and whose children are among the brightest scholars in our public schools.” Their mode of conduct was anarchist “of the word,” not “of the deed.” In fact, they were little involved in the town’s electoral political and did not significantly influence the mainstream trade union movement in Barre. Their political views were shaped by their experiences in Italy, and after arriving here they stayed closer to political developments back home than Barre. Frequent communications and periodic return trips to northern Italy by many workers sustained the distant focus.

Barre’s anarchist ferment began to fade prior to World War I. The decentralized structure of the granite cutting industry in the early 1900s, in terms of scale of production, had provided the local economic resonance for the anarchist impulse with its emphasis on decentralized control of production. But the industry’s rapid grown and mechanization of production in those same years rapidly drove small manufacturers out and brought increased centralization. Also, as time passed, Barre’s Italian anarchists became more rooted in the immediate community, and ethnic group interest superseded class interests. Thus the militant Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), although influenced by avowed anarchists, came to be seen as “too radical” for the anarchists of Barre. When the IWW sought places to send strikers’ children during the famous and lengthy IWW-led strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1912, Barre workers organized a Lawrence Strike Committee and took in several of the strikers’ children for the duration of the strike. But after the strike was ended, when its leaders came to Barre to thank the Italian community and make a pitch for syndicalism, their appeal drew little support. In the 1920s when Sacco and Vanzetti, Italian immigrants and self-proclaimed anarchists, were charged with murder and armed robbery in Massachusetts, “Barre was never so stirred up”; fund raising drives were conducted and when the two men were finally electrocuted in 1927, workers walked off their jobs in sheds and quarries. Again the incident seems to have been less a demonstration of anarchist sympathy than Italian ethnic solidarity in a difficult time. In Barre, as elsewhere, anarchism as a viable social movement no longer existed.

—Gene Sessions

For further reading:

Paul Demers, “Labor and the Social Relations of the Granite Industry in Barre” Thesis (B.A.)--Goddard College, 1974. Photocopy, Baily/Howe Library, University of Vermont.

Vermont labor history [sound recording] : Barre granite industry [interviews conducted by Paul Demers] (1972). 16 sound cassettes : analog, mono.; 1/8 in. + transcript (1 v).

Emma Goldman, Living My Life (New York: A. A. Knopf, 1931).

Barre Museum, Aldrich Public Library, Carlo Abate, “A Life in Stone” (1987).

Citation for this page

Woodsmoke Productions and Vermont Historical Society, “The Anarchist Movement in Barre, 1920,” The Green Mountain Chronicles radio broadcast and background information, original broadcast 1988-89. https://vermonthistory.org/anarchist-movement-in-barre-1920