Interpreting the Past Through Manuscript Collections

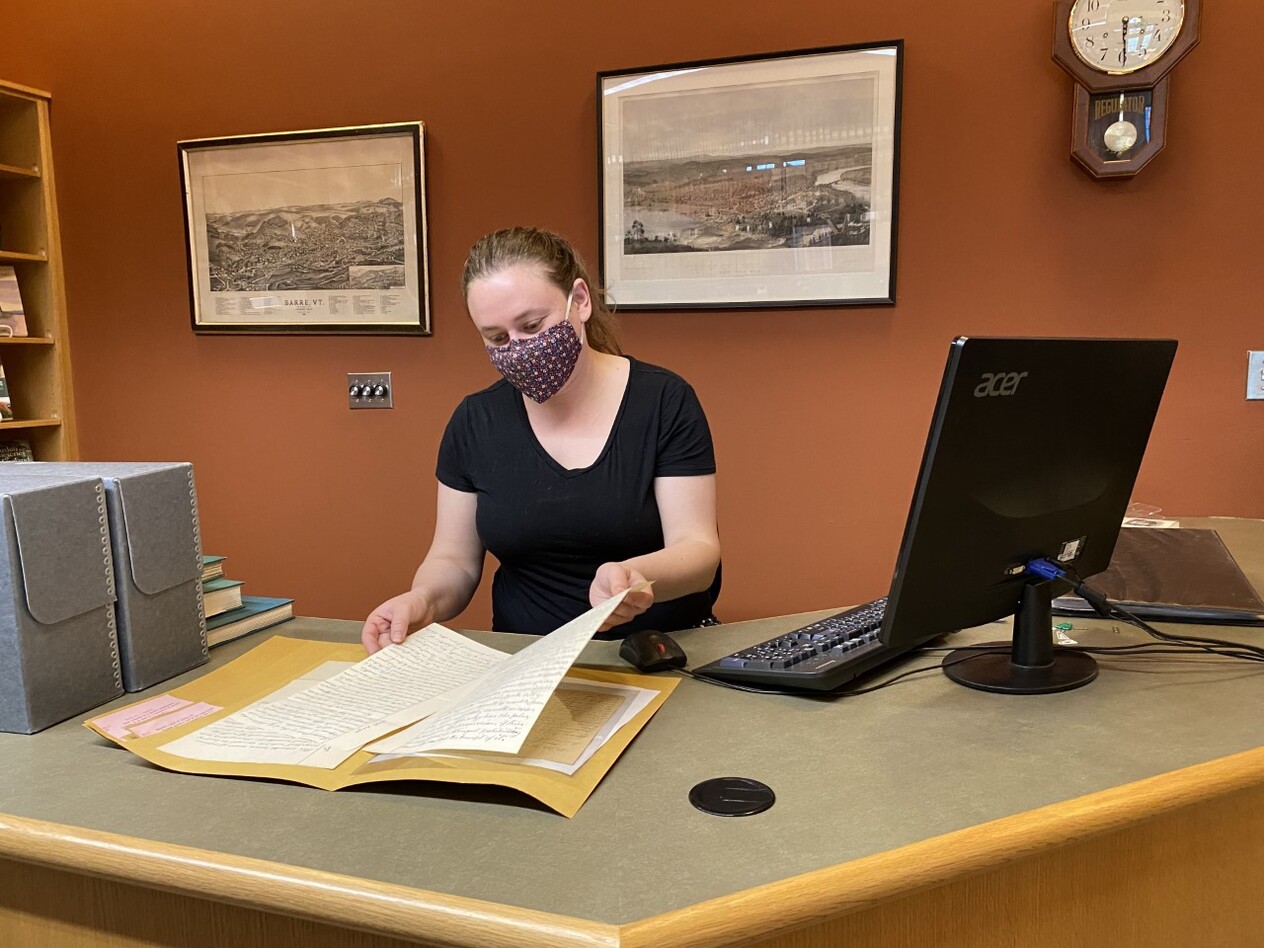

VHS Assistant Librarian Marjorie Strong was cataloging 1940s correspondence between a man and his niece when she realized his writing was more than just a personal perspective of his life. Said Marjorie, "he was typing on a typewriter, but he was typing phonetically. I could hear his voice; I could hear how [he] pronounced things."

The Leahy Library in Barre is home to an extensive assortment of materials in addition to manuscript collections. They have many books, of course, but also photographs, printed ephemera, maps, films, and audio recordings. This anecdote illustrates how the Leahy Library's collection of manuscripts opens a window into the rich history of Vermont while adding nuance to the story.

Manuscript collections make up the second-largest category in the library after books. They comprise unique documents such as letters, diaries, notes, deeds, and other original source material centered on Vermont History. Although these types of collections are sometimes referred to as archival collections, Librarian Paul Carnahan is careful to note that archives are typically the records of an organization's operations, not the personal documents found in a manuscript collection.

The broad story of Vermont's past can be understood through the minute details of people's lives preserved in manuscript collections. These ostensibly mundane fragments of yesterday, the moments often taken for granted, can tell us a lot about those who came before us and how they viewed their world.

It is not only the content of these texts that provide insight but how and on what they are written. A favorite story of Marjorie's involves a soldier composing a letter from inside his tent, "the handwriting was in ink and nice, and then it turns into pencil, and it's all crabbed and crazy on the page. His tent collapsed and he kept writing!" The soldier finished soon after his tent failure, but his letter still has the power to transport the reader back in time.

Kate Phillips, VHS Cataloger and Metadata Librarian, has a particular interest in the history of paper. Changes in paper type correlate with changes in culture, and those observations can speak volumes about the author and their environment. For example, one might discern between the writings of an officer versus an enlisted man, as officers had more access to paper. Likewise, unconventional choices can tell a story. When paper was in short supply, soldiers in their quarters might remove the wallpaper and put it to good use.

Sometimes, library staff has only fragments of a story and must do detective work filling in the blanks. Kate recalls a collection of jumbled slips of paper clipped together and linked only by town names. They turned out to be records of barters made at a dry goods store. In this instance, the collection came with other identifying information, but that is not always the case.

One can learn much from these manuscripts, but it is often up to the larger imagination of the researcher to bring meaning to the files.

About her stack of receipts, Kate says, "I have no idea how somebody might use it, but somebody might come in with a great idea. And so, our job is to make sure they're able to find out we have this thing and find out where it is. The researcher may see something in it that's entirely different from what I see."

Sometimes, library staff is surprised by what they learn when interacting with researchers.

Marjorie recalls a library visitor fascinated by scrapbooks, which are often dismissed as inconsequential by researchers. This researcher was intrigued by scrapbookers' selections– why they chose those newspaper clippings, poems, and prayers, and the confluence of spiritualism and politics. Commonplace books – personal collections of information such as recipes, quotes, poems, musings, and the like- can also be subject to this bias. The library has a considerable collection of women's commonplace books, one of which contains excerpts from poems by Phyllis Wheatley, the first African American author of a published book of poetry. Through a researcher's work, it was determined the owner of the commonplace book was acquainted with Wheatley. Marjorie says she now catalogs these types of manuscripts with more attention to context than she had in the past.

How does the library staff know how to catalog? Their goal is to anticipate the needs of researchers by using standards adhered to by libraries across the country. In the Leahy Library, researchers can apply the same methods used at other research facilities to find what they need.

According to Paul, this takes time, but the extra effort makes records accessible to everybody. Accessibility is achieved, in part, by the volunteers who dedicate their time to the library's cataloging efforts. Says Paul, "A lot of collections come in in a real mess. [Volunteers] look for commonalities within the materials in the collections." Volunteers might work on "arrangement and description"- putting a multigenerational collection into folders, identifying a common theme, and creating a finding aid.”

Finding aids are an organizational tool with detailed information about a collection. They are created by volunteers and catalogers who do additional research to determine who the people are. Finding aids are the synthesis of a collection and how the people inside are remembered. These days, finding aids are converted to PDFs that are discoverable through the library’s online catalog (catalog.vermonthistory.org), online search engines, and a special plugin on the VHS website at vermonthistory.org/manuscripts. Says Paul, "as librarians, we like the controlled vocabulary, the subject headings, the carefully formulated approach to information of an online catalog. But that's not necessarily the way people are searching. We have to meet people where they are, and keyword searching Google is where they are."

Cataloging manuscripts is part of the library’s ongoing efforts to give more exposure to the VHS’s collections to researchers online. Browse some of the VHS’s digital collections.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2021 issue of our member magazine, History Connections. To get it in your mailbox, become a VHS member.